The Belgian Canals

By Tim Boykett

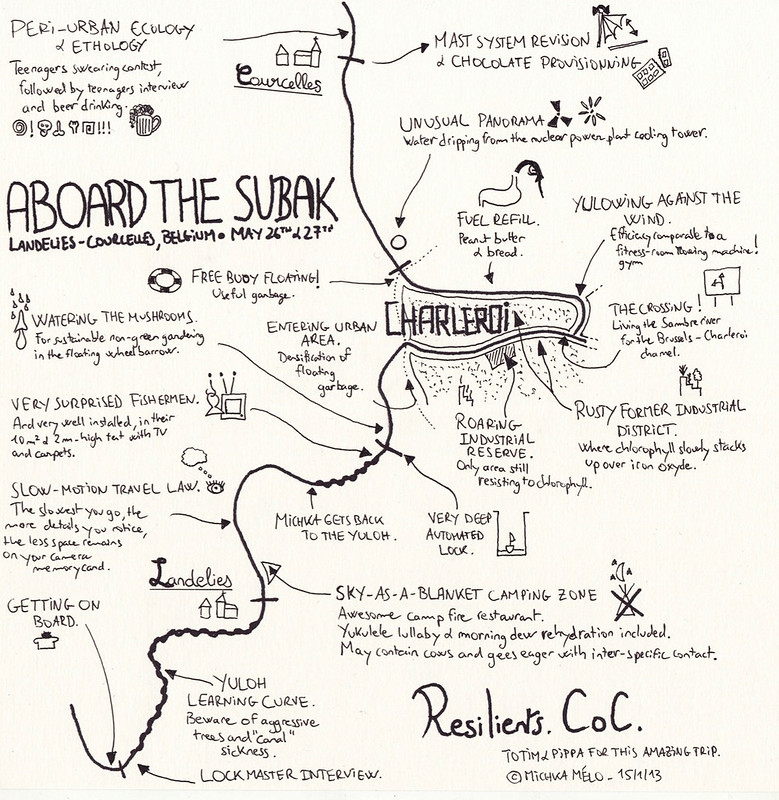

The Belgian canal trip was envisaged as an exploration of northwestern Europe's waterways, overwhelmingly subject to human planning and control historically up to the present day. Originally routed along the northern part of Belgium along the border with the Netherlands, we decided to avoid this area owing to the extreme industrialisation and dangers present there. Instead we departed on the Sambre river, just within the French border. On our boating expeditions both in Australia and on the Danube we had originally planned to cross either state or country borders, but in each case this had proved impossible. So here at least we crossed one border – the unmarked one between France and Belgium.

Joined from the outset by Marthe van Dessel and assisted by Markus Luger, we got the Subak set up with mast lowered for the low bridges. The industrial wastelands of Wallonia and northern France were our scenery for the next ten days of the journey – starting with the collapsing factory walls on the border, drunken unemployed workers, and drifting rubbish.

We overnighted in a small harbour, where our first interviewees were an older couple who had been living on the canals for months at a time after the man had retired from the merchant marines. Her agoraphobia was well-suited to the confined spaces of the vessel.

They brought up a theme that echoed through many of our subsequent interviews. We were confronted repeatedly on the Belgian waterways by people calling for their urgent maintenance. The river banks, the canals, the aqueducts and locks were all in states of partial and increasing disrepair. Passage through certain canals was blocked due to the danger of collapsing structures. Some waterways were slowly filling up with sand, mud and debris.

This can be attributed to their falling into disuse, with the autobahns and trucks taking over the barges' prior role as the mass carrier of choice. But returning to barge transport is also filled with problems. Whether it is the plethora of dead fish that litter the canals, their bodies scarred by propellors or the low bridges and governmental reluctance to widen the canals as seen in Halle where some retailer chain wants to move a part of its distribution back onto the canals, there are things that say that boat transport is not desired.

Michka Mélo joined us for a few days on the river as well. He brought an engineering approach to yulohing, investigating it in terms of angles of incidence and arcs of motion.

In Wallonia and on the fringes of Flanders as we approached Brussels, French was a language barrier. We had ample help from Marthe and Michka, and managed after they left with our rudimentary language skills to get a few interviews down.

We encountered drunken youths encouraging us to “suck my cock” in multiple languages. We saw operating factories amidst vast industrial wastelands. A church in a converted barge. Shallows in the canals bubbled with decomposing organic waste or chemical poisons – we weren't sure which. Well-wishers on bicycles delivered us coffee, we were shown old boat yards, and we heard stories, anecdotes, impressions, hopes and fears about the future of the waterways. A fellow waved us down to give us a copy of a newspaper in which an article about us had appeared; drivers hooted horns; cyclists waved; and we won't forget the image of a red-headed kid standing on a car seat peering down at us through the window.