This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Groworld Game

Context

Groworld was concerned with exploring people's relationship with plants. Computer games are a powerful medium for suspending one's belief in other, imaginary worlds. The focus of the groworld game was to explore the use of computer games to allow players to become closer to the plant world.

Foam were working on this project with two other groups, Tale of Tales and SixToStart. Both of whom have experience working on projects which use games technology to explore specific experiences and situations.

And as a game project, we were sometimes explicitly, at other times implicitly tackling these issues:

- What is the depiction of plants and growth within existing games?

- Should this be a scientific simulation, if not how do we avoid this?

- What is an art game? Are we making one?

Problem/Aim

The aim was to explore a number of different areas:

- The player taking on the role of a plant, and therefore in some sense becoming one

- Using plants as inspiration as an organisation model, (e.g. through the use of decentralised technologies such as peer to peer networking)

- Using games as a method of story telling

- Describing the complexities of permaculture through a game

- Using multiplayer cooperation in a similar way as plants growing together for mutual benefit in permaculture guilds

- Using plant guilds as a framework for a game world's structure

- Developing and using human-plant interfaces as way to directly couple the game with living plants

- Find ways of augmenting living plants with information from the game

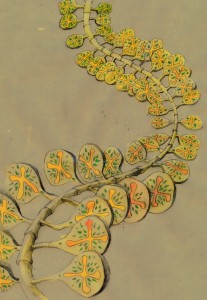

- Use the groworld drawings as inspiration and incorporate them into the game in some way

- Incorporate the game with a groworld gardeners website to share a database of information

The problems we had to solve were involved with the design of the game, what most suited the aims we had in mind. On a course level, decisions had to be made based on questions like:

- 2D or 3D, both or neither?

- Conceptual, metaphorical, schematic?

- Immersive, descriptive, detailed, fully animated?

- Online, in browser or downloadable app?

Given these decisions, we also needed to decide what technology would be the most appropriate to use. From there we could go on to develop some game mechanics and work on an overall design.

The expected outcome was a downloadable multiplayer game which would be associated with an installation involving living plants. Plants in the game world would mingle with the real plants by means of projection, and sensors which would read signals from the plants and their environment.

Methods

We met for many design gatherings, mostly in the foam studio. Between the meetings we communicated via the groworld mailing list, skype, and during active development we made use of a dropbox folder to share images, movies and executable game prototypes. Foam also made use of a git repository for sharing code and associated data. Images of drawings and screenshots were posted and categorised on flickr and movies, prototypes and images we also posted on personal blogs by those involved.

The work seemed to go through various changes of pace and focus. The start was about discovering the roles and expertise within the group, while at the same time trying to pin down a design, or at the very least a broad common theme that we could all work within. During this first phase we were also trying to answer the question of what technology we could work on together.

The very first experiments I tried were very much simulation based, simulating photosynthesis by growing lsystem plants with genetic algorithms in order to solve particular problems - in this case getting the most energy from a light source by angling and positioning leaves.

In our first meeting it became apparent that of course, we were making a game, and of far more interest was how people could create plant shapes - not simulating their growth. During the course of the meeting (and the eurostar trip back afterwards) I worked on an lsystem sketching program that would create the same rules the simulation had, but using mouse input rather than the iterative genetic approach.

I also wanted to try and take a well known game, and put it into a vegetal world. I also wanted to try playing a game from a plant’s POV, so I chose Tetris, and warped it around the roots of a tree. The blocks represented nutrients coming in from the soil, which you fit together to grow your plant which is in the middle of the screen. Each row (or circle in this case) completed made your tree grow a little more.

During the second meeting this underwent some play testing, and Theun summed up the problem nicely - you don't think about plants playing this game, you think about Tetris. This made it clear to me that we couldn't really take a normal game mechanic or existing game world and theme it to fit our needs - we needed an original world with new game mechanics.

At this point I was convinced that we should be making a 2D game. It seemed like we would need a huge amount of material to make a world that was detailed and full of growing life. Producing this much content in 3D was going to be difficult, so it seemed much better to me to stick to 2D where we could use sprites and textures. This would also make the choice of a platform a bit easier to make, possibly an online one.

I spent some time working on combining images of parts of plants combined with lsystems to see how detailed we could get. The results were much better looking than the 3D lsystems, and easier to control artistically.

Meanwhile as a group we were also trying to describe in general what the eventual game could look like and how it could work. We discussed for long periods of time, and it seemed that people had quite clear ideas but we seemed to have difficulty somehow merging them together into a clear shared design. However, after one of these long sessions Auriea and Michaël posted their tale of the plant dungeon. A lot of the ideas here ended up influencing the rest of the project.

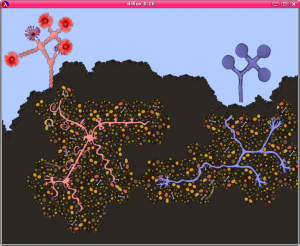

Taking the ideas of a split between below and above ground from the plant dungeon, and a more cellular approach to being a plant, I had a go at making another quick game prototype.

The idea is to pull energy from photosynthesis into the ground where it can mix with nutrients to cause further growth. Cells can be dragged around with the mouse and connected together. Photosynthesising cells (the green ones of course) convert photons (the little sparks) into energy which they use to divide, and pass on to the structural cells (the brown ones) which hold the plant together. You need to get energy from photons hitting the green cells above ground to the blues ones underground to make new cells. The problem I found pretty quickly was that it wasn't a particularly fun experience, moving little cells around with the mouse is tiresome, and it just felt like hard work. I wanted a 'higher level' approach - plants probably don't have to consider where all their cells go.

It was at this point that I had to pack up all these prototypes and take them to foam’s contribution to Ghent’s “The game is up” festival (how to save the world in 10 days). We talked about, eat, drew, grew and philosophised over plants. I took the opportunity of getting the public to test all the game prototypes so far, and make some new ones by process of ad hoc livecoding, sometimes as they were being played. This was a great experience for me, but quite exhausting! Importantly as a group we tried playing some relevant games (including the excellent Nobi Nobi Boy) at Tale of Tales headquarters nearby.

The most popular game to come from the Ghent experience was a dancemat powered pollination experience which seemed particularly to catch the imagination of the younger game testers.

On a more technical note it also became apparent that despite having a sketch system working, lsystems were not going to provide us with the artistic control we needed to get the variety of plants that were being discussed. I did some research into putting drawings of small components of plants together in a way that was determined by the drawing, rather than an algorithm. This system was called pluggable plants which I continued to use in game prototypes for a while as a nice way of getting interesting plants without tons of complex detail.

As a group we were now getting more in depth on the design process. We had the groworld story which gave us a good description of a world in which to base the game. However, we were still hitting problems with a shared idea of what the end product would be. It was getting urgent we brought these strands together, so we tried various techniques to help:

- Making 'user stories' of what playing the game would feel like

- Collaboratively drawing the game on a massive sheet of paper

- Building mockups of the game in Blender using bits of drawings and game prototypes we'd already made.

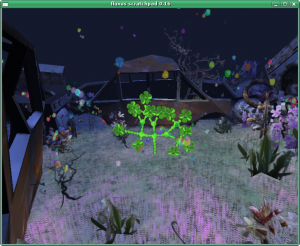

I was getting concerned with a technical aspect of the game, the multiplayer part. With it looking more likely we were going to use fluxus more and more, and I had no experience of this area. Time for yet another prototype - the groworld multiplayer prototype. This used jabber as it's communication protocol, which had the advantage that we would not need to maintain our own server. I also wanted to try a more developed world to put the game in, and had an idea of an old scrapyard being magically brought back to life by plants, so spent a few days learning blender and fixing bugs in the fluxus importer.

The project seemed to get a new surge of activity as Tale of Tales had time to spend on active development. A 2D hexagonal growth board game seemed like a suitable mechanic for us to concentrate on as a group. After initially agreeing to use the Blender game engine which seemed good common ground between us, the pressure of time meant that results were going to be quicker coming if we worked in environments we were most comfortable with. The idea was that at the end of their time ToT had available for development, we would be able to take the core ideas of the game, plus any assets such as textures and models and continue in a free software environment such as fluxus.

Despite this divide of environments, this phase was probably the most effective in terms of shared development on the project. I started playing with ideas with a hexagonal lattice and we were able to share techniques, such as a method for disguising hexagons with curves and tentrils of a root system I found from looking at islamic patterned tiles and a figuring out a bit of binary maths.

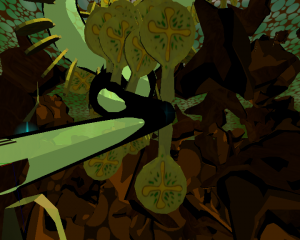

However, as we approached the end of the time which ToT were able to actively develop, there was a sense of disillusionment at the game we had created. The was mainly due to a feeling of gardening, rather than growing - managing a plant, rather than being one. I started to look again at creating a 3D world which concentrated on making the player see the world as a plant does, therefore called 'plant eyes'. While this meant that a lot of the things we had made were not transferable to the 3D world (the pluggable plants for instance) after making a quick prototype it was so nice to be back inside a space rather than looking down at one, it seemed the right decision.

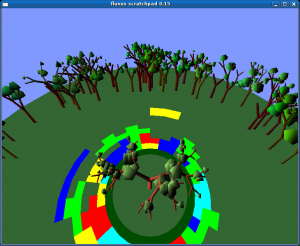

The first plant eyes prototype:

The general idea is that you start of inside the seed of your plant. You can then grow outwards and down into the earth, in order to locate and absorb nutrients with your roots, or upward and out into the air and attract insects with flowers that grow on your branches.

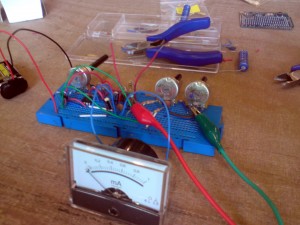

I now had a period of intense work on this last game prototype. There were also now more and more inspirational drawings being worked on for the groworld almanac. Nik and I were also given the opportunity to look at an area which had been put to one side so far - the human-plant interfaces. We led a workshop on plant sensing in Berlin, in which we developed hardware to sense light, moisture and temperature from a plant's environment, and software for communicating it with the game world. We also investigated sensing of plant phenomena of a more mysterious and spiritual nature, involving onions - but our results were inconclusive.

The plant eyes prototype grew and started taking on more elements from the sketches by Theun and Lina:

In age old game development tradition, I tried to add complexity while keeping the cpu usage down - such as these branches built out of camera facing sprite geometry:

I tried as much as possible to take things from the earlier design decisions, such as Auriea's idea of the path of growth being created by the player with a dotted line, these turned into trails of 'breadcrumbs' which the roots grew along as the player's camera returned to the seed. In an attempt to incorporate the plant guilds, I added different types of plants, and corresponding nutrients which would give the player different abilities. Once these nutrients were absorbed, you would grow different leaves, flowers, potatoes, forks and trumpets. Taking much appreciated advice from a game tester in her 80's I added plenty of supporting life for the plants, worms in the soil, spiders on the ground and butterflies in the air.

As we approached the final date of the grig event, work increased, I became more focused on the event and creating an installation. I stopped working on the multiplayer and game distribution elememnts and focused on the overall look and playability. I added gamepad input for an easier way for people to play the game. Tale of Tales were also in full development mode again, and were speedily working on more 3D prototypes based on models inspired by the drawings in the groworld almanac, in which you inhabited a garden you could navigate around and look at the plants as they grew.