This is an old revision of the document!

Scenario Methods

This page is an evolving, non-exhaustive collection of different steps that can be used in scenario building, different methods that we (could) use and links to interesting people/project using scenarios in their work.

An overview of the whole process written for novice scenario builders can be found in How to Build Scenarios by Lawrence Wilkinson. Interesting Ten Rules for Creating Awful Scenarios by Jamais Cascio, can be used as a checklist of what NOT to do in scenario building.

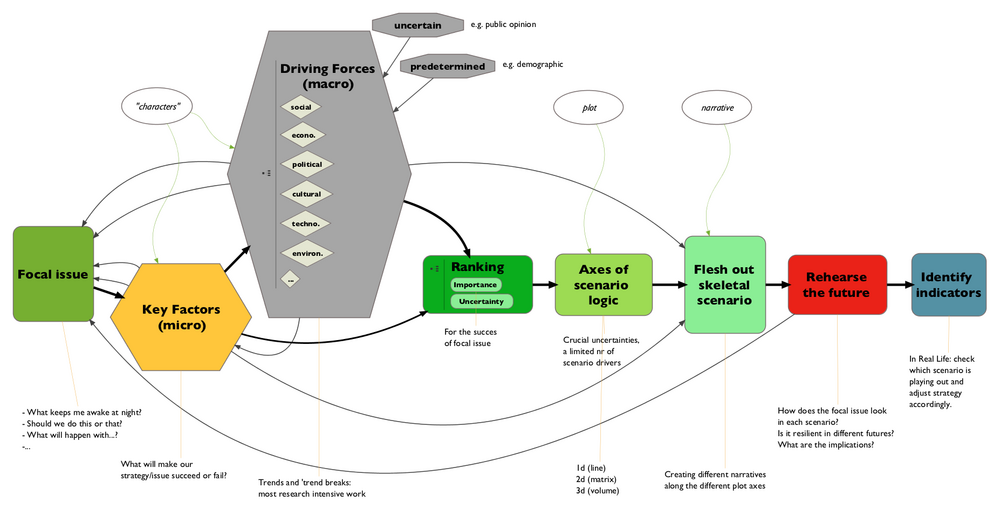

There are many descriptions of scenario planning methods, with the biggest difference being whether the scenarios are designed to be exploratory (multiple alternative scenarios for different possible futures), or normative (designing a desired scenario, then figuring out what needs to be done in order to get there). When working with normative scenarios the most important task is 'backcasting' or 'retrocasting' as we prefer to call it (see chapter about this lower on this page). With exploratory scenarios a lot of the time is spent on creating the elements of the scenario based on the present of the internal and external environment, as well as forces that can influence change in both. Most scenario methods revolve around approximately the same phases: (1) delineating the space/issue/question (2) identifying elements of the scenario (factors, drivers, trends, measures, actors, events…) 3) selecting a reasonable amount of elements 4) projecting the elements in the given future in the form of multiple scenarios and 5) using scenarios to (re)design decisions, strategies and actions in the present. There are many different variations of scenario building flow. We list a few below:

Joseph Coates wrote “Today the question of what scenarios are is unclear except with regard to one point-they have become extremely popular. Many people see scenarios as forecasts of some future condition while others disavow that their scenarios are forecasts. Yet looking at scenarios that do not come labeled as forecasts or non-forecasts. It is difficult to tell them apart. The purpose of the scenario is at a meta level, since the scenario usually does not speak for itself in terms of its purpose.” More in Scenario Planning. Another early in depth overview of How Companies Use Scenarios was written by Mandel and Wilson.

The scenario building exercise (step 1-6) in the prehearsal pocket guide is based on the method by Peter Schwartz in The Art of the Long View. On this page Schwartz summarises the scenario building steps.

Michel Godet writes in The Art of Scenarios and Strategic Planning: “we strive to give simple tools that may be appropriated. However, these simple tools are inspired by intellectual rigor that enables one to ask the right questions. Of course, these tools do not come with a guarantee. The natural talent,common sense, and intuition of the futurist also count!”

The “Cone of Plausibility, according to Charles W. Taylor, “serves as an enclosure that circumscribes the thought process of the players. The strength of their thought process to build these scenarios and to hold them together as they proceed outward in time is a counterforce to the pressures of wild cards to disrupt the cone. Scenarios within the cone are considered plausible if they ad|here to a logical progression of trends, events, and consequences from today to a predetermined time in the future”

Anna Maria Orru and David Relan wrote The Scenario Symphony for the Resilients project, containing a whole range of scenario creation methods, including the dynamic panarchy and temporal model.

More methods are described in the Futures Research Methodologies chapter 13 by Jerome C. Glenn and The Futures Group International.

Finally, an interesting avenue to explore are remote scenario planning workshops using various online collaboration tools. Jamais Cascio describes here how he conducted a virtual scenario workshop, Noah Raford describes another experiment in online scenario planning.

Below we explore different elements of scenario building, ask questions that emerged from our practice and investigate methods that might be used to improve the process.

Preparation beforehand

What can we/participants prepare for a scenario workshop beforehand?

Commonly the people organising the workshop will “Work on identifying major drivers, trends and events should be initiated ahead of the first workshop: this is an opportunity to draw on relevant horizon scanning work and other analysis. Ideally this work will be synthesised into a format which can be accessed easily by workshop participants, either as preparatory material or at the workshop itself. Material researched at this stage should include a mix of thematic material, together with analyses of broader trends.” The Horizon Scanning Centre (pdf)

other possibilities:

- Interviews, questionnaires for participants beforehand

- Collective horizon scanning (facilitators, participants)

- Insight meditation

- …

What are the ideal settings (e.g. room size per person) for a scenario workshop?

- a large, long smooth wall or white/blackboard (at least 4-5 metres long, longer is better)

- enough space for all participants to sit comfortably in a circle or semicircle

- additional space for 3-5 breakout groups (a large working table, chairs, a wall or another surface to hang stuff up

- social space with comfortable seating (e.g. sofas, bean bags, cushions) & refreshments (if possible for the whole group, otherwise for at least 4-5 people)

- empty space (at least 3x3m for spreading stuff out, or doing physical/spatial sessions)

- big windows with natural light

- facilitation table (with various materials)

- 'library' or books, media, magazines, images… related to the topics discussed

- easy access to outdoor spaces

- …

Key question

How to craft good questions?

How to better structure/encourage designing the core question?

Questions encourage an inquiring mind

Why does it seem more difficult to phrase questions rather than stating problems?

“In nearly all cases it should be possible to formulate the purpose of the scenarios work as a question. If this proves difficult, this is often an indication that the work will not be taken up when completed, even if it is of a good quality.” -The Horizon Scanning Centre (pdf)

Plotting the present situation

What are different ways to map-out the present situation surrounding the key question?

When to use this step?

When can it be reduced/removed? When is it more important to focus on this step (observe, then interact as permaculture teaches us) than to work on possible future scenarios?

What does a 'futurism without prediction' look like?

A few ideas on non_predictive_strategy

When does it help to talk about things that are fixed, or constraints that exist?

- in a workshop where the group had a pressing need to resolve a situation, talking about what is fixed quickly gave a picture of what was still possible to change and what was the space in which the group could move to find solutions to a blockage

- on the other hand, in more open-ended workshops (say in the beginning of projects) talking about what's fixed created some discomfort (or perhaps it was just unclear what we meant by fixed)

Key factors

What are different ways to visualise and cluster the relationships between key factors

- Force Field Analysis by Kurt Lewin, where the key question is placed in the middle, forces exerting pressure for the change on the left, and against the change on the right.

- “interrogate anomalies: data or incidents that seem anomalous - that somehow “don’t fit”, seem weird or don’t make sense, should receive immediate attention. They could be pointers to a shift in the system as a whole” From: http://silberzahnjones.com/2012/10/04/crafting-non-linear-strategy-the-nature-of-the-problem/#more-799

What do we mean by key factors?

- internal (local) drivers of change

- success criteria (what will make my question succeed or fail)

Change Drivers

- how much analysis is appropriate for the types of scenarios and prehearsals we’re making?

- how can we make assumptions and guesswork more apparent (i.e. indicating how drivers can be based on an assumption, guess or 'fact')?

- what is the relevance of facts and data related to macro trends in experiential futurism?

- how can we have a more constructive discussion about the macro trends which results in something more meaningful than a list of assumptions?

- how do we look at drivers as dynamic forces? should we be looking at responses to trends rather than trends in general? (nouns → verbs)

What are existing ways of discussing trends with groups of people?

- See various methods on the horizon scanning page

- should we make our own STEEP (or related) cards to avoid the 'business bias'? probably, if we have the time - and focus on long term trends only + add wild cards (random images/words/tarot/playing cards…)

- are there other well understood methods to group trends other than the customary STEEP (in which cultural changes seem to be clumped in with social or political)? see horizon scanning

- is there another way to look at large scale changes aside from trends (without having to do a PhD in each of the changes)?

- how effective are these methods and how can we usefully evalute them?

Ranking critical uncertainties

- what are different ways in which this is done by others? most approaches i could find use numbers, or conversation.

- Morphological Analysis could be a great way to work with a large number of clustered drivers, that can be combined in different ways to select a smaller set of important and/or quickly create basic scenario skeletons. The foodprints ruler from FoAM Nordica works on a similar principle.

Scenarios

When to use one, two, three or more axes

- Two axes method: Scenarios generated using the ‘two axes’ process are illustrative rather than predictive; they tend to be high-level (although additional layers of detail can subsequently be added). They are particularly suited to testing medium to long-term policy direction, by ensuring that it is robust in a range of environments. Scenarios developed using this method tend to look out 10-20 years.The Horizon Scanning Centre (pdf)

- Branch analysis method: The ‘branch analysis’ method is suited to developing scenarios around specific turning-points that are known in advance (e.g. elections, a referendum or peace process). This approach works best for a shorter time horizon: generally up to five years.The Horizon Scanning Centre (pdf)

- Cone of plausibility method: offers a more deterministic model of the way in which drivers lead to outcomes, by explicitly listing assumptions and how these might change. Of the three techniques, this approach is most suitable for shorter-term time horizons (e.g. a few months to 2-3 years), but can be used to explore longer-term time horizons. It also suits contexts with a limited number of important drivers.The Horizon Scanning Centre (pdf)

- Morphological Analysis could be a great way to work with a large number of clustered drivers, that can be combined in different ways to select a smaller set of important and/or quickly create basic scenario skeletons. The foodprints ruler from FoAM Nordica works on a similar principle. ”

- More on Field Anomaly Relaxation

(After reading several papers about MA/FAR, I wonder what is the difference between MA and FAR?)

How to better structure building scenario skeletons with guiding questions (which questions could be generalised)?

From scenarios to story-worlds

- what techniques can we use to flesh out the scenarios into interesting stories?

- “a day in the life of…” (a character in a scenario, or one character in different scenarios)

Retrocasting

“The best kinds of stories are about how you get from here to there, not just what there looks like.” –Jamais Cascio

Searching for present signals, asking the question “how to get from here to there”. Aka Backcasting Backcasting: Backcasting starts with defining a desirable future and then works backwards to identify policies and programs that will connect the future to the present.

However with retrocasting/retrotesting or scenario testing (as we also call it sometimes) we don't look at exclusively at a desirable future, but at different possible futures resulting from scenario building, and attempt to identify signals in the present that might point to the future moving in this or that direction.

What tools can we use to structure scenario testing?

Cause & Effect Diagram: “The cause and effect diagram is used to explore all the potential or real causes (or inputs) that result in a single effect (or output). Causes are arranged according to their level of importance or detail, resulting in a depiction of relationships and hierarchy of events.” In scenario testing this could be used not as 'cause and effect', but how to get there from here (note down a topic from the scenario, then work backwards to see what would have to happen to make it happen).

Another interesting possibility is to abstract principles from a scenario and retrocast from them. In this article they suggest not to use scenarios at all, but to work from agreed upon sustainability principles.

- what are important things to focus on?

Visualising

Which methods could we use to visualise scenarios?

- moodboards

- collages

- storyboard

- newspaper with headlines

- video mix

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinterest|pinterest board (or similar collective online pinboard)

Prototyping

- which methods could we use to prototype possible futures?

More on possible_futures_parallel_presents and experiential futures

Prehearsals

- how to design them?

- how to host them?

- how to evaluate them?

continue research on prehearsal methods

Follow-up

- How can we follow-up what happens to the groups after we finish the workshops (especially to understand what happens to commitments to actions and preferred possible futures)?

- How much do we need to be involved in the follow-up?

Futures research methods

From: Identifying systems' new initial conditions as influence points for the future

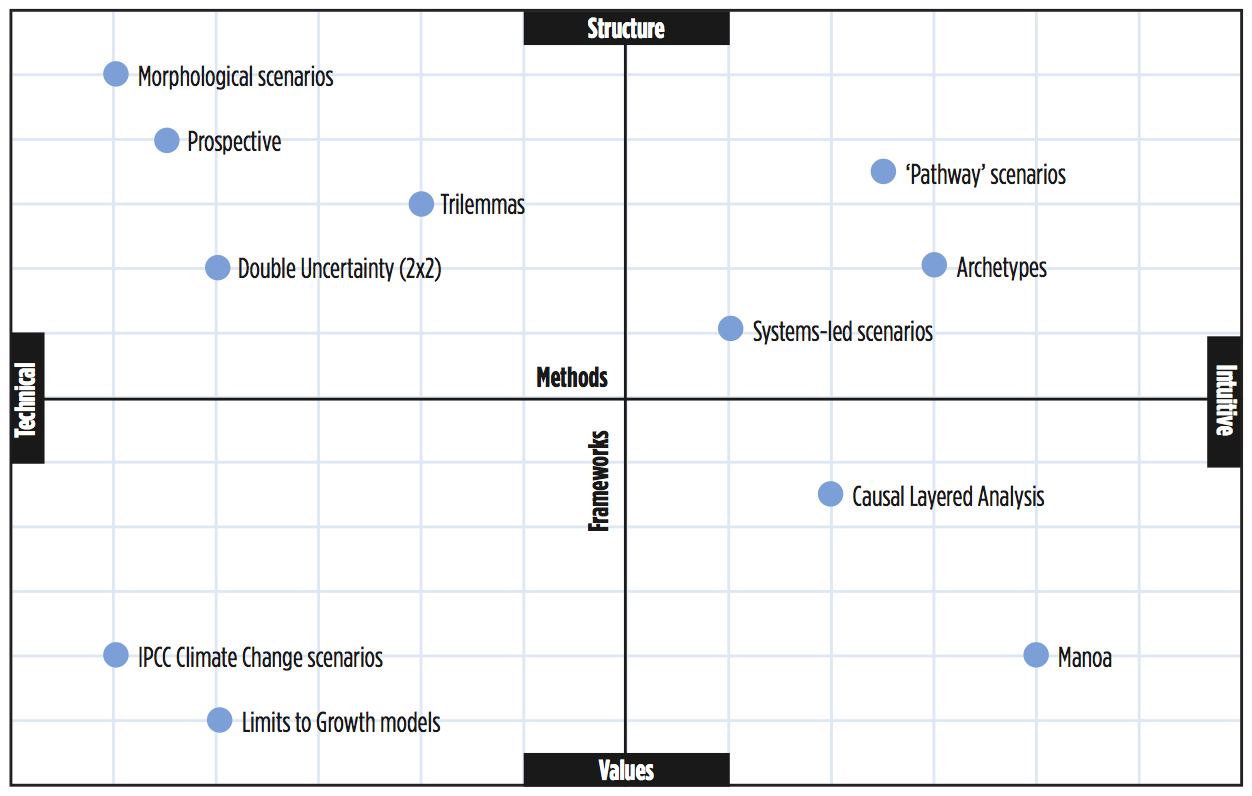

Mapping scenarios techniques. (Source: Andrew Curry)

Analysis, Summaries and comparisons

Using four different scenario building methods: the 2×2 matrix approach; causal layered analysis; the Manoa approach; and the scenario archetypes approach. “This exploratory comparison confirmed that different scenario generation methods yield not only different narratives and insights, but qualitatively different participant experiences. ”

Curry, Andrew and Wendy Schultz (2009), “Roads Less Travelled,” Journal of Futures Studies, Vol. 13(4). http://www.jfs.tku.edu.tw/13-4/AE03.pdf

“The paper to review all the techniques for developing scenarios that have appeared in the literature, along with comments on their utility, strengths and weaknesses. […] eight categories of techniques that include a total of 23 variations used to develop scenarios. There are descriptions and evaluations for each.”

Bishop, Peter, Andy Hines and Terry Collins (2007), “The current state of scenario development: an overview of techniques,” Foresight, Vol. 9(1). http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/aboutus/whatwedo/PolicyAnalysis/UKHigherEducation/Futures/Documents/current_state_of_scenario_development_FORESIGHT.pdf

“In my experience, scenario planning is an interpretive practice – it’s really closer to magic than technique. … Look long enough, hard enough, and the pieces will fall into place. Magic is a very difficult thing – most people spend their whole life cutting magic out.” –Napier Collyns